EER and Ear Nose and Throat

The EER and ear nose and throat symptoms page is an in depth explanation of what you may already be suspecting as an infant acid reflux related situation. We hope this page helps answer some questions. Such as "Why does my baby get ear infections all the time?, Why does my baby seem to have a constant cold?, Why does my baby seem to be struggling for air?"

Intermittent reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus is a normal physiological process. It occurs because of transient relaxation of the sphincter located where the esophagus connects to the stomach. Gastroesophageal reflux is considered to be abnormal or pathologic if it produces symptoms, and is then referred to as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

FIGURE 1

How extra-esophageal reflux arises.

Arrows show path of reflux from stomach.

UES = upper esophageal sphincter and

LES = lower esophageal sphincter.

GERD (Gastro Esophageal Reflux Disease) is a well-documented and common occurrence among adults, but during the last twenty years, it has been increasingly recognized as a clinical entity among children and infants. GERD most commonly results in vomiting, abdominal or chest pain, heartburn, arousal from sleep, and regurgitation (spitting up).

If gastric reflux reaches the level of the pharynx (throat) by moving past both the lower and upper esophageal sphincters (as shown in Figure 1), it is termed extra-esophageal reflux (EER). Evidence is accumulating that EER can be a factor in disorders of the upper and lower airway in both adults and children. (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 1,2)

Infants may be especially predisposed to reflux-related problems because they have relatively more reflux events than adults. In a survey of 948 infants, it was found that nearly 50% of babies less than 3 months old had reflux events that resulted in regurgitation or spitting up at least once a day (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 3). The number increased to a maximum of 67% of 4-month-olds. By 1 year of age, percent of infants with daily regurgitation events was less than 5%.

Although symptoms of GERD are fairly easy to diagnose, extra-esophageal reflux is a more difficult diagnosis. “Silent reflux” or atypical reflux in which the patient has no gastrointestinal symptoms is very common in children with upper and lower airway complaints. Determining the involvement of EER requires verifying its presence by some diagnostic methodology.

A methodology commonly used to determine whether a person has gastroesophageal reflux is to measure acidity by means of a pH-detecting “probe” placed at the lower esophageal sphincter (LES. Fig 1). However, traditional pH probes placed to detect acid reflux at the LES can easily overlook EER in the child. A significant percentage of children who have EER show normal pH data from probes placed at the LES (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 4,5). Therefore, a better approach to EER diagnosis is to monitor pH in the pharynx or upper esophagus. Although pharyngeal probes provide excellent measures of EER, they are uncomfortable for some children because the procedure involves insertion of rubber tubing through the nose. Parents also shy away, especially once they learn the tubing must stay in the nose for 24 hours.

An innovative alternative for diagnosing EER is the Bravo pH capsule. This capsule is wireless, and is placed in the upper esophagus just behind the upper esophageal sphincter (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 6). The Bravo system has been a very good way to measure upper esophageal reflux without any tubing.

In this chapter we focus on how EER results in damage to cells and

tissues of the larynx and upper respiratory tract. We also discuss a

number of ear, nose, throat, and laryngeal disorders commonly

encountered in pediatric patients and examine evidence for the role of

EER in causing or exacerbating these conditions.

How Reflux Affects the Airway

The larynx, or voice box, acts as a two-way valve to prevent aspiration of food and liquids into the lungs during swallowing. During breathing, the larynx is open, allowing air to move in and out of the lungs via the trachea, but during swallowing, the larynx closes off the airway.

Even so, the proximity of the airway to the esophageal entrance makes the potential for reflux to enter the airway very high in certain situations. When a person is lying flat, refluxing gastric contents can readily flow into the esophagus to the level of the larynx and throat. Babies are especially prone to EER because their lower esophageal sphincter doesn’t reach maturity until 18 months and therefore doesn’t always function fully to keep gastric contents in the stomach.

FIGURE 2a, 2b, 2c

Acid-protective mechanisms of the esophagus.

A. Peristalsis pushes gastric contents back into the stomach.

B. Cross-section of esophageal epithelium shows glands that secrete a protective layer of mucus.

C. Closeup shows layers of stratified squamous epithelial cells, which secrete acid-neutralizing bicarbonate ions.

Acid and the digestive enzyme pepsin are responsible for the damaging effects of reflux. Stomach tissue is most protected against their damaging effects, but even so, erosions and ulcers can develop. While not nearly as resistant to the effects of acid and pepsin as the stomach tissue, the esophagus is adapted to handle some acid exposure that occurs due to intermittent physiological reflux. Peristalsis, which is rhythmic, wavelike movement of the esophagus, helps push reflux back into the stomach (Figure 2a). The esophagus secretes mucus that forms a protective barrier against the corrosive effects of the reflux. The esophagus is also lined by a specialized layer of cells called stratified squamous epithelium that secretes bicarbonate ions, which can neutralize the acid (Figure 2b and 2c). Even these protective mechanisms in place, acid may still penetrate the epithelial layers and irritate nerve endings, which results in the sensation of “heartburn.”

Unlike the stomach and esophagus, the respiratory tract is extremely sensitive to the damaging effects of gastric fluids. The respiratory tract is lined by a cell layer called pseudo-stratified, ciliated columnar epithelium, which is very different in structure from the epithelium in the esophagus (Figure 3).

Respiratory epithelia possess tiny hairs called cilia that perform a protective function. The sweeping action of the cilia keeps the airway clear by removing mucus from the respiratory tract. The cilia also help eliminate infectious and allergenic materials from the body because any bacteria, viruses, dust, pollen or mold that float onto the cilia also are swept out of the airway.

FIGURE 3

Cellular structure of the upper respiratory tract.

A. Cross-section of respiratory epithelium.

B. Closeup of respiratory tract showing transformation of ciliated epithelial cells to unciliated squamous cells in response to EER.

When repeatedly exposed to reflux, the respiratory columnar epithelium sometimes will change into stratified squamous epithelium like that found in the esophagus (Figure 3). Although more resistant to the damaging effects of reflux, squamous cells do not possess cilia. By causing the loss of cilia, EER compromises an essential cleansing process in the respiratory tract.

Sometimes when explaining to patients the difference between the ability of the esophagus and the airway to tolerate reflux, we use the analogy of the esophagus being a rubber hose and the airway being tissue paper. While not entirely accurate, it does paint a picture of the relative sensitivities of the two.

Although direct irritation of the respiratory tract by acid and pepsin

can bring about the signs and symptoms of airway disease, reflux can

also have an indirect, or referred, effect on the airway even if it

never leaves the esophagus. This indirect effect comes about because the

esophagus and airway are connected to a common central nerve called the

vagus. When acid refluxing into the lower esophagus interacts with

special structures called receptors, nerve impulses can arc backwards

along the vagus to cause spastic closure of the larynx (laryngospasm).

This reflexive response of the airway to reflux is yet another way in

which the body protects itself from aspiration.

Common Ear, Nose, and Throat Conditions Resulting from EER

A

number of ear, nose and throat disorders commonly encountered in

children and infants have been found to be associated with EER. For some

disorders, the association is likely causative, that is, the acid and

pepsin in reflux are directly responsible for the signs and symptoms

associated with the condition. For other disorders, EER is not

necessarily causative, but the presence of reflux can make the signs and

symptoms much worse. In a few cases, it has been speculated that

worsening of symptoms is because the condition increases the likelihood

that reflux can escape the esophagus and get into the airway. In other

words, rather than EER causing the condition, the condition causes EER.

This section provides an overview of the signs and symptoms of laryngeal

and upper airway disorders commonly encountered in pediatric practice

and how EER can bring about or aggravate these disorders. The role of

anti-reflux therapy in treating these conditions is also discussed.

Effects of EER on the larynx, or voice box

The larynx is anatomically just in front of the esophagus and therefore is very susceptible to the effects of EER. Multiple sites of the larynx can be irritated and cause a number of different signs and symptoms. Some of these include: chronic cough, hoarseness with or without vocal cord nodules, laryngeal ulcers, and vocal cord dysfunction.

Cough

Cough is one symptom commonly associated with irritation of the larynx. Cough is a protective reflex that removes irritants or infectious organisms such as those causing pneumonia. Irritants are detected by "cough receptors," which are nerve endings located in the larynx and other parts of the respiratory tree. Receptors are also located in the naso- and oro-pharynx (throat), the sinuses, and the ears (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 7). Through coughing, the airway tries to relieve itself of its acid load as best as it can. However, persistent cough can itself further irritate the airway. EER is an important agent in chronic cough, that is, coughing that continues for 3-8 weeks. Excluding infectious diseases, EER is third most common cause of chronic cough in children and the most common cause in infants 0-18 months old (ref: 8).

FIGURE 4

Top and side views of the larynx afflicted with EER-associated conditions compared to a normal larynx. Top views are what an ENT physician would see looking down a child's throat using a laryngoscope.

Arrows point to affected regions.

• vocal nodules, swellings on the vocal chords;

• laryngomalacia, collapse of the entrance to the larynx upon inhaling;

• subglottic stenosis, narrowing of the area below the vocal chords.

Hoarseness

Hoarseness is another symptom that can be associated with the deleterious effects of reflux on the larynx. Hoarseness is a general term for any abnormal voice quality, but voice quality can be further described as breathy or harsh, husky or rough, strident, or coarse. Though voice intensity varies with the amount of a air pressure against vocal cord resistance, voice quality is primarily determined by length, tension, strength of movement, mass, or position of the vocal chords (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 9). Any aberration of length or tension of the vibrating segment, mass, posture, or strength of the vocal cords may result in hoarseness. In a study of children aged 2-12 years old who had chronic hoarseness for more than 6 months, 70% of them were found to also have GERD (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 10). When researchers directly examined the vocal cords of these children, one child's vocal cords looked normal, but the remainder had a variety of abnormalities that included cord swelling, nodules (Figure 4), and evidence of healing ulcerations.

Paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction (PVCD)

Another abnormality of the vocal cords that can be associated with

damage from reflux is paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction (PVCD). During

breathing, normally functioning vocal cords should move into an open

position to allow free flow of air through the larynx. In PVCD, the

vocal cords are inappropriately closed with breathing. When cord

movement is not synchronous with breathing, voice quality isn't

affected, but it creates a sensation of airway obstruction. PVCD can be

quite distressing and mimic asthma or severe inspiratory airway

obstruction. In rare cases, it has resulted in placement of a

tracheotomy tube to assist breathing. PVCD is most commonly found in

teenagers (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 11), but cases masquerading as bilateral vocal cord

paralysis have been reported in newborns (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 12). Reflux therapy

resolves PVCD and may be curative (11, 12).

Stridor and laryngomalacia

Another sign of a problem in the airway is stridor, which is a coarse, high-pitched sound when breathing in. Stridor results from turbulent, rapid air flow through a narrowed portion of the airway. Because a number of airway disorders can cause stridor, a physician should explore all possibilities when evaluating patients with stridor, but EER may play a significant role in those conditions most commonly associated with stridor.

Airway abnormalities present at birth are responsible for 87% of stridor cases in infants (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 13). The most common of these congenital abnormalities is laryngomalacia (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 13). Laryngomalacia refers to an abnormal floppiness of the laryngeal tissues just forward of the vocal cords at the airway entrance. Stridor results because upon inspiration, these floppy tissues get pulled into the opening of the airway, narrowing the diameter of the opening by partially blocking it (Figure 4). Although inspiratory breathing is noisy, breathing on expiration is normal, as is the voice.

Parents may notice their baby has noisy breathing at birth, but usually laryngomalacia-associated stridor becomes most noticeable at 1-2 months when the infant is becoming more active and making more demands on the airway. Respiratory effort and noisy breathing typically get worse before they resolve, usually by 18 months of age.

Two studies have shown a strong association between laryngomalacia and gastroesophageal reflux. In one study, 80% of infants with stridor due to laryngomalacia also had gastroesophageal reflux (ref: 14). In another, more recent study, the severity of laryngomalacia was shown to be directly related to the severity of gastroesophageal reflux (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 15).

The co-association of laryngomalacia and reflux may be a common manifestation of neuromuscular immaturity that simultaneously results in flaccid airway structures and poor esophageal sphincter tone (ref: 14), which may explain why symptoms often disappear as the child matures. Another possibility is that EER is a secondary effect of the laryngomalacia in which the inspiration of air against the narrowed airway creates of suction effect that pulls reflux up and out of the esophagus (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 14). Either way, reflux can cause a worsening of symptoms of laryngomalacia because the inflammation and swelling of the laryngeal tissues results in still greater obstruction of the airway. Aggressive reflux therapy is recommended (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 5).

Croup and subglottic stenosis (SGS)

Reflux may also play a role in children who suffer from repeated cases of croup. Symptoms of croup include stridor, a barking cough, hoarseness, and difficulty breathing. In children older than a year, an isolated case of croup often comes on the heels of an upper respiratory infection and is usually due to a virus-induced inflammation of the larynx. However, infants less than 1 year old who have repeated cases of croup may have a condition called subglottic stenosis (SGS), which is an abnormal narrowing of the subglottis, a region of the larynx located below the vocal cords (Figure 4). Different severities of SGS exist and are graded 1-4, with a Grade 1 being the least severe and Grade 4 representing nearly complete obstruction of the airway.

Infants can be born with SGS, but they can also develop SGS due to physical injury to the larynx. Physical injury includes damage caused by acid reflux. Studies in animals in which direct application of acid to the larynx resulted in the formation of SGS confirms a causal association between EER and acquired SGS (ref: 16). One study has shown that infants who have recurrent cases of severe croup requiring hospitalization are more likely to have an additional diagnosis of reflux (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 17), and another reported that 80% of children undergoing surgery to repair their SGS had at least one positive test for EER (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 18).

A mild, Grade-1 SGS that would normally not be noticed can be exacerbated by EER or recurrent viral illness. Children with Grade-1 SGS may spontaneously improve as they get older, and often anti-reflux medication is all that is needed to keep the airway sufficiently open until the SGS resolves. Severe SGS requires surgical intervention, but anti-reflux medications help improve the success rate of these surgeries and reduce the need for additional operations, presumably because healing can occur more readily in the absence of acid (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 19, 20).

Effects of EER on the pharynx, sinuses, and ears

Not only can EER irritate the larynx, it can also irritate the pharynx (throat). Reflux can flow up into the oro- and naso-pharynx and may even reach the nasal and sinus cavities (Figure 5). EER has accordingly been implicated in a number of symptoms and disorders of the pharynx, nose, sinuses, and ears. Pharyngeal signs and symptoms associated with or caused by EER include: sensations of choking or a lump in the throat with or without constant throat clearing, adenoid enlargement, rhinosinusitis, eustachian tube dysfunction and middle ear infections.

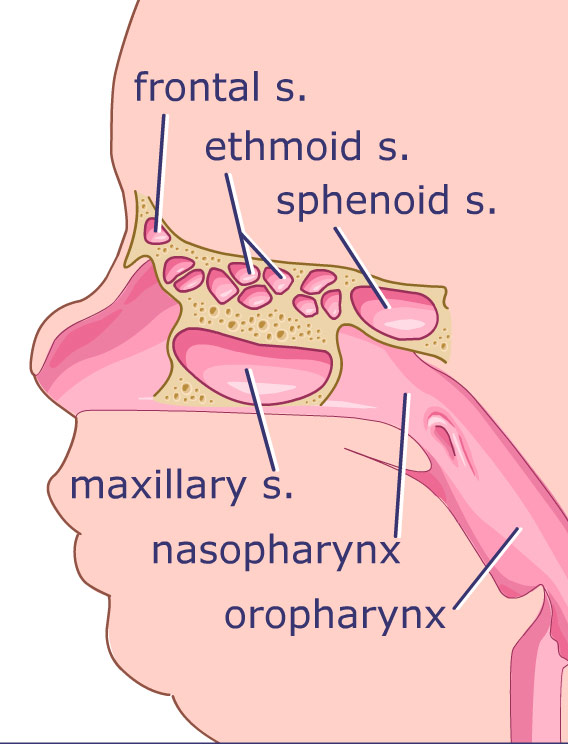

FIGURE 5

Due to the close proximity of the esophagus to the airway, EER can get into the larynx, the pharynx, and even into the eustachian tubes that connect to the ears.

Globus pharyngeus (lump in the throat)

Inflammation of the pharynx can result in globus pharyngeus, which is the medical term for having a sensation of a lump in the throat (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 9). The sensation is most notable between swallows. EER is the most common underlying factor, although other anatomical, physiological, and psychological factors should be considered.

Enlarged tonsils

Enlarged adenoids, which can block the nasal airway, may also be attributable to EER in very young children. In a study of children less than 2 years old who underwent surgery for removal of enlarged adenoids, 42% also had a GERD diagnosis. By contrast, GERD was diagnosed in only 7% of a control group of children getting surgery for insertion of ear tubes but whose adenoids were normal. The association between reflux and adenoid enlargement was even stronger in children age 1 or less. In this age group, 88% of those requiring adenoidectomy had a GERD diagnosis, whereas only 14% of the control group getting ear tubes had a GERD diagnosis (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 21).

FIGURE 6

Front and side views of the sinuses, which are cavities located in the bones of the face. They are connected to the nasal cavity by narrow passages. EER can cause inflammation of the sinuses. Infection is often a secondary complication.

Reflux may be a factor in inflammation of the nose and sinuses. Called rhinosinusitis, this inflammation is caused by obstruction of the final common pathway of the maxillary, ethmoid, and frontal sinus tracts (Figure 6). Although infection is often present, it is not typically the primary underlying factor for rhinosinusitis. Rather, infection occurs secondarily because the impaired drainage due to swelling, or edema, of sinus and nasal tissues creates an ideal environment for the growth of bacteria. Anything irritating the sinus and nasal tissues can result in swelling of tissues: Allergies, cigarette smoke, recurrent viral infections, and EER. Edema from EER is a common cause of sinus obstruction (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 22). People with chronic sinus problems often have corrective surgery. However, Bothwell et al. (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 23) found that 89% of children who underwent reflux therapy in addition to maximal medical management of allergy and other irritants could avoid sinus surgery.

Otitis media (middle ear infection)

Like the sinuses, the ear has natural openings that must remain functional to prevent problems. As in rhinosinusitis, the development of middle ear infections (otitis media) is a secondary complication that results from impaired function of the eustachian tube. Studies using animal models have shown that exposure of the middle ear and the eustachian tube to acid and pepsin results in failure of the eustachian tube to perform its dual function of sweeping out secretions and modulating pressure within the ear (EER and ear nose and throat=ref: 24, 25). In a study examining patients who had chronic ear problems, treatment with the anti-reflux medication omeprazole resulted in complete resolution of symptoms (ref: 26).

Conclusion of EER and Ear Nose and Throat Symptoms

EER is a topic to be investigated along with other important causes of ENT problems such as allergy, immune deficiency, smoke exposure, and other yet-to-be defined factors. EER sometimes is a difficult diagnosis to make and is even more difficult if not suspected. However, if EER is discovered to be an underlying or contributing problem, instituting reflux therapy often can control or even eliminate symptoms altogether.

Contents of the EER and Ear Nose and Throat page originate from the Maci-Kids website and

from Dr. Jeffrey Phillips' research in treating infants with acid

reflux. Accreditation's listed below.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Pamela S. Cooper, Ph.D., for writing and editorial assistance in revising the manuscript.

Credits: Marcella Bothwell, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Otolaryngology and Department of Pediatrics. Jeff Phillips, Pharm D, Associate Professor, Department of Surgery. Stacy Turpin,Medical Illustrator, Department of Surgery

References:

1. Rosbe KW, Kenna M, Auerbach AD. Extraesophageal reflux in pediatric

patients with upper respiratory symptoms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg. 2003;129:1213-1220.

2. DeVault KR. Extraesophageal symptoms of GERD. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(suppl 5):S20-S32.

3. Nelson S, Chen E, Syniar G, Christoffel K. Prevalence of symptoms

of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy: a pediatric practice-based

survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:569-572.

4. Little JP, Matthews BL, Glock MS, et al. Extraesophageal pediatric

reflux: 24-hour double-probe pH monitoring of 222 children. Ann Otol

Rhinol Laryngol. 1997;169 (suppl.):1-16.

5. Mathews BL, Little JP, McGuirt WF Jr, Koufman JA. Reflux in infants

with laryngomalacia: results of 24-hour double-probe pH monitoring.

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:860-864.

6. Bothwell MR, Phillips J, Bauer S. Upper esophageal pH monitoring of

children with the Bravo pH capsule. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:786-788.

7. Irwin RS, Boulet LP, Cloutier MM, et al. Managing cough as a

defense mechanism and as a symptom:a consensus panel report of the

American College of Chest Physicians. Chest. 1998;114(2 Suppl

Managing):133S-181S

8. Holinger LD and Sanders A.D. Chronic cough in infants and children: an update. Laryngoscope. 1991;101: 596-605.

9. Bluestone, CD, Stool S, Kenna, M, et al., ed. Pediatric Otolaryngology. 4th ed. Philadelphia:Saunders; 2003.

10. Kalach, N, Gumpert L, Contencin P, Dupont C. Dual-probe pH

monitoring for the assessment of gastroesophageal reflux in the course

of chronic hoarseness in children. Turk J Pediatr. 2000; 42:186-91..

11. Powell DM, Karanfilov BI, Beechler KB, Treole K, Trudeau MD,

Forrest LA. Paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction in juveniles. Arch

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126: 29-34.

12. Heatley DG,Swift E. Paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction in an

infant with stridor and gastroesophageal reflux. Int J Pediatr

Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;34:149-151.

13. Hollinger LD. Etiology of stridor in the neonate, infant, and child. Ann Otol Rhinol Larygnol. 1980;89:397-400.

14. Belmont JR, Grundfast K. Congenital laryngeal stridor

(laryngomalacia): etiologic factors and associated disorders. Ann Otol

Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93: 430-437.

15. Giannoni C, Sulek M, Friedman, EM. Duncan NO 3rd. Gastroesophageal

reflux association with laryngomalacia: a prospective study. Int J

Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;43:11-20.

16. Little FB, Koufman JA, Kohut RI, Marshall RB. Effect of gastric

acid on the pathogenesis of subglottic stenosis. Ann Otol Rhinol

Laryngol. 1985;94:516- 519.

17. Waki EY, Madgy DN, Belenky WM, Gower VC. The incidence of

gastroesophageal reflux in recurrent croup. Int J Pediatr

Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;32:223-32.

18. Yellon R, Parameswaran M, Brandom B. Decreasing morbidity

following layrngotracheal reconstruction in children. Int J Ped

Otorhinolaryngol. 1997;41:145-154.

19. Halstead LA. Role of gastroesophageal reflux in pediatric upper

airway disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:208-214

20. Halstead LA. Gastroesophageal reflux: a critical factor in

pediatric subglottic stenosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

1999;120:683-688.

21. Carr MM, Poje CP, Ehrig D, Brodsky LS. Incidence of reflux in

young children undergoing adenoidectomy. Laryngoscope.

2001;111:2170-2172.

22. Loehrl TA, Smith TL. Chronic sinusitis and gastroesophageal

reflux: are they related? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

2004;12:18-20.

23. Bothwell MR, Parsons DS, Talbot A, Barbero GJ, Wilder B. Outcome

of reflux therapy on pediatric chronic sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck

Surg. 1999;121:255-62.

24. White DR, Heavner SB, Hardy SM, Prazma J. Gastroesophageal reflux

and eustachian tube dysfunction in an animal model. Laryngoscope.

2002;112: 955-61.

25. Heavner SB, Hardy SM, White DR, McQueen CT. Prazma J. Pillsbury HC

3rd. Function of the eustachian tube after weekly exposure to

pepsin/hydrochloric acid. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:123-129.

26. Poelmans J, Tack J, Feenstra L. Prospective study on the incidence

of chronic ear complaints related to gastroesophageal reflux and on the

outcome of antireflux therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol.

2002;111:933-938.

Return to GERD Symptoms from EER and Ear Nose and Throat page